Belly Breathing - General Overview of Breathing

- Jackie Allen

- Sep 25, 2020

- 12 min read

Hey hey readers! In this new series, I will discuss the what, why, and how of belly breathing. Belly breathing goes by many names, including diaphragmatic breathing (which I personally think is misleading because we always use our diaphragm when we breathe, but that's just my two cents!) and abdominal breathing. I personally prefer the term "belly breathing," so I will use that term most often in this series.

I briefly discussed belly breathing and the neural consequences of deep breathing in my Autonomic nervous system series. You might want to check that post out at some point because the information is related to the topic in the current series (link here).

In part 1 of this series, I will give an overview of breathing in general, the various muscles used during breathing, the different modes of breathing, and the relationship between breathing and emotional state (i.e. the "what"). Stay tuned for future parts of this series that will review the scientific evidence behind belly breathing (i.e. the "why") and different ways to practice belly breathing (i.e. the "how").

A Super Simple Crash Course in Breathing Physiology

Since we are going to be talking a TON about breathing, I want to do a relatively quick overview of the basics of respiration (i.e. breathing).

The lungs, various muscles of respiration, and your nervous system are the “main players” involved in breathing. The lungs are located in the thorax (i.e. the upper trunk), just above the diaphragm. The bilateral lungs are masses of nonmuscular tissue that is spongy, porous, and highly elastic. Because of this elasticity, the lungs return to their relaxed, or resting, position when they are stretched (i.e. during inhalation) or compressed (i.e. during forced exhalation).

The lungs cannot contract by themselves during respiration. Instead, the lungs passively expand and shrink in size as a result of the contraction and relaxation of the respiratory muscles (described in the next section), leading to gas exchange between the air and the lungs. During inhalation, the lungs expand in size (i.e. lung volume increases), and the pressure inside the lungs decreases (based on Boyle’s Law, which says that the pressure and volume of a gas are inversely proportional - i.e. if volume goes up, pressure goes down, and vice versa). Now, the atmospheric pressure (i.e. outside the lungs) is greater than inside the lungs. Since gases flow from areas of high to low pressure, air flows into the lungs – hence inhalation. During exhalation, the lungs shrink in size (i.e. lung volume decreases), and the pressure inside the lungs increases relative to atmospheric pressure. Thus, the air flows out of the lungs (i.e. it flows from high to low pressure) – hence exhalation.

Obviously, you breathe in/out all day long, even when you are sleeping, and your breathing rate and depth changes many times throughout your day, based on your internal and external environment. For example, sometimes your breathing rate increases to fulfill increased oxygen demands in your body, such as during exercise. Other times, you need more muscle power when you exhale, such as during speaking (so called "speech breathing"), heavy lifting, vomiting, or defecation (i.e. pooping). And other times, such as when you are stressed out or panicked, your breathing may become fast and shallow, using many muscles of the upper trunk and back to assist. And sometimes your breath is quiet and restful (so called "quiet breathing"), such as when you are relaxing or feeling calm and centered. Based on the type of breathing you are doing, your nervous system will recruit different muscles to assist to different degrees.

The diaphragm is definitely the most important muscle of respiration and arguably the most important muscle in the body, for without your diaphragm you stop breathing and cease to live. While the diaphragm may be the most important breathing muscle, other muscles in the chest, thorax, and abdomen are also important players during breathing. Let’s chat about some of these muscles in more detail because we will revisit these muscles several times over the course of this blog series.

Muscles of Inhalation

The main function of inspiratory (i.e. inhalation) muscles is to increase the lung size. The primary muscles of inhalation, the diaphragm and external intercostals, are active to some degree with each and every breath. The accessory muscles of inspiration assist, or help out, when the breathing demands increase (e.g. during exercise).

Diaphragm. The diaphragm is the primary muscle of inhalation – without it, you do not breathe. It is a thin, dome-shaped, unpaired muscle that separates the lungs and heart from the other organs, forming the floor of the thoracic cavity. When the muscle fibers of the diaphragm are activated during inspiration (i.e. inhalation), they develop tension and shorten. As a result, the “dome” moves downward and flattens. This downward motion of the diaphragm produces both an expansion of the lungs and a displacement of the abdominal contents, leading to an outward motion of the front wall of the abdomen. The diaphragm also displaces the rib cage as it contracts. Since the volume of the lungs has increased (and consequently pressure inside the lungs decreased), oxygenated air is drawn into the lungs. The opposite occurs when you exhale. During exhalation, the diaphragm relaxes, returning upward into the lower rib cage, resuming its dome-like shape. The front wall of the abdomen then moves back inward and softens. Since lung volume has now decreased (and consequently the pressure inside the lungs increased), carbon dioxide-rich air flows out of the lungs. The diaphragm is always active during any type of breathing (quiet, speech, or exercise), although it might not be activated maximally based on your breathing patterns (more on this later).

External intercostals. These primary muscles of inhalation are a series of muscles situated between each of the ribs. When the external intercostals contract, they actually elevate the rib cage, increasing the size of the thoracic cavity, and subsequently, the lungs. The external intercostals are usually active during both quiet and speech breathing.

Accessory muscles of inspiration. The accessory muscles include muscles of the chest (e.g. pectoralis major/minor), neck (e.g. sternocleidomastoid, levator scapula, scalenes), and upper back (e.g. trapezius, rhomboids). These muscles are active during exercise, periods of high stress, and sometimes during speaking. At rest (aka during quiet breathing), these muscles should not be active (more on this later).

Muscles of Exhalation

The main function of expiratory (i.e. exhalation) muscles is to decrease lung size. During quiet breathing, exhalation is typically a passive process without muscular contraction – the elasticity of the lungs causes them to naturally return to their baseline size, the diaphragm muscle relaxes and moves upward into its normal position, and gravity pulls downward on the rib cage returning the ribs to their resting location. During speech breathing or exercise, however, the muscles of expiration work together with the passive forces of elasticity and gravity described above to compress the abdominal organs and depress the lower ribs. The main muscles for exhalation include the internal intercostals and the abdominal muscles (discussed below).

Internal intercostals. The internal intercostals are a series of muscles situated between each of the ribs, located deep (i.e. further away from the skin) to the external intercostals. The internal intercostals are generally only active during speech breathing and exercise.

Rectus abdominis. The rectus abdominis muscle is formed by large vertical, paired muscles that extend from the lower part of your hip bones to the sternum (i.e. breast bone); it is your "six pack" muscle right on the front of the belly area. The rectus abdominis is generally only active during speech breathing and exercise. When it contracts, it compresses the abdomen, forcing the diaphragm to move back to its resting position.

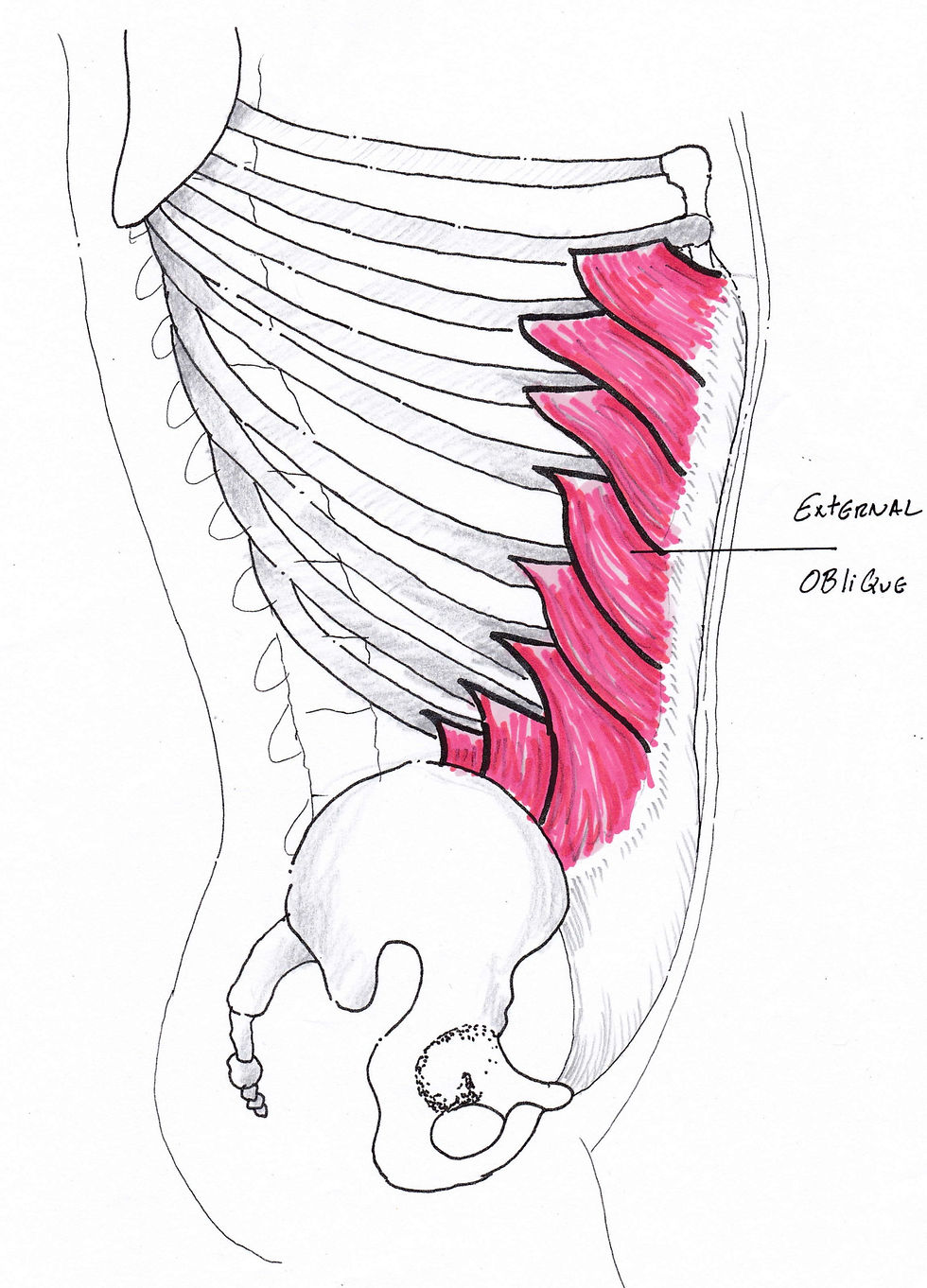

External obliques. The bilateral external obliques are fanlike muscles that extend from top of the hip bones to the lower ribs. These muscles are generally only active during speech breathing and exercise. When the external obliques contract, they help to lower the rib cage and compress the abdomen.

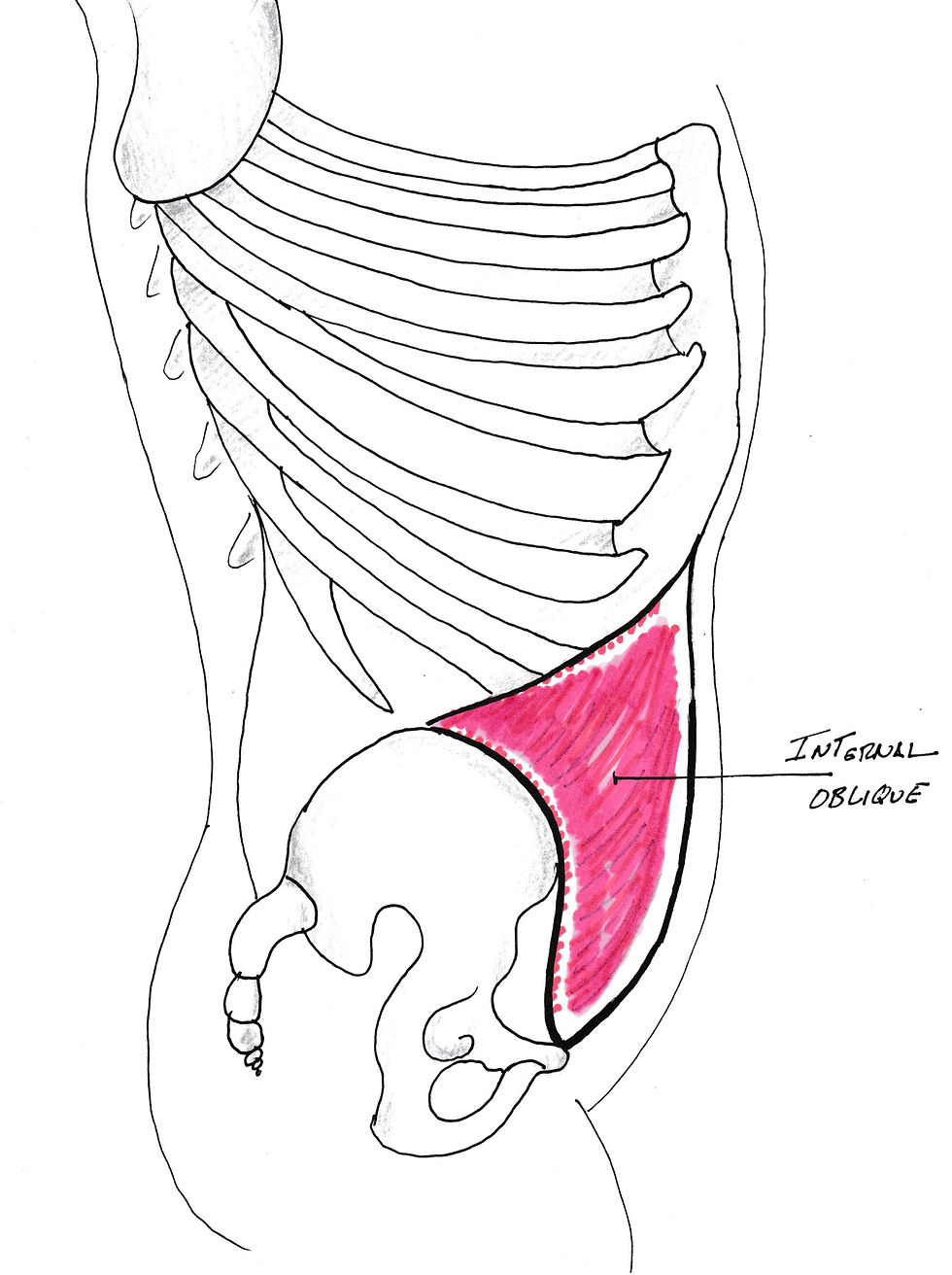

Internal obliques. The bilateral internal obliques are also fanlike muscles that extend from the top of your hip bone to your lower ribs. The internal obliques are generally only active during speech breathing and exercise. When the internal obliques contract, they help to lower the rib cage, thereby reducing the size of the lungs.

Transversus abdominis. The transversus abdominis is the deepest (i.e. the furthest away from the surface of the skin) of the abdominal muscles. It is a broad muscle that extends from the vertebral column (i.e. spine) to the front of the lower belly, wrapping around your belly area like a cummerbund . The transversus abdominis is generally only active during speech breathing and exercise. When it contracts, it compresses the abdomen.

Different Modes of Breathing

There are three modes, or styles, of breathing, including belly (aka abdominal), thoracic, and clavicular breathing. Each style uses different muscles of respiration in different ways and to different degrees, and each mode affects the nervous system, and consequently the muscles' resting tone, in different ways. Let's chat about each one in more detail.

Clavicular breathing. Clavicular breathing is also known as stress breathing or shoulder/neck breathing, and it unfortunately is the "go-to" breathing pattern most people use in our modern society. This mode of breathing uses very little range of motion (ROM) from the diaphragm, and instead recruits your chest (e.g. pectoralis major, etc.), neck (e.g. levator scapulae, scalenes, etc.), and upper back (e.g. upper trapezius) muscles. These chest, neck, and back muscles are designed to help with breathing OCCASIONALLY, but using these muscles for breathing "on the regular" can lead to increased stiffness and tension in the muscles. This can lead to back and neck pain, which is so common these days. Obviously, clavicular breathing is okay if you are in legit danger or out of breath and need to increase your breathing and heart rate quickly. However, habitual clavicular breathing keeps your sympathetic nervous system turned "on" most, or all, of the time (for more information on the sympathetic nervous system, click here). This keeps your heart rate and blood pressure higher than normal, leading to a whole host of health issues, and it increases the resting tone, or tension, in your muscles, reducing the mobility of your muscle movements (for more information on the factors that influence joint mobility, click here). Additionally, clavicular breathing can wreak havoc on your vocal quality (umm, glottal fry anyone?) since it is the least efficient mode of breath to support speaking and singing.

Thoracic breathing. Thoracic breathing, sometimes called chest or ribcage breathing, uses the diaphragm, intercostals, and some chest (e.g. pectoralis major/minor) and upper back muscles (e.g. rhomboids), along with muscle bracing, or tension, in the abdominal muscles. This muscle bracing does not allow the diaphragm to descend fully on inhalation, which is why more rib cage, chest, and back muscles are recruited. While this mode of breathing is surely better than clavicular breathing, it can still "turn on" the sympathetic nervous system (similar to clavicular breathing), putting you in a fight, flight, or freeze response. That being said, using this mode of breathing sometimes is actually quite good for the mobility of your thoracic spine and ribs. Additionally, thoracic breathing is super important when you are exercising, especially during weight lifting or sports, because you have to brace your midsection to keep you spine safe. Thoracic breathing is typically the style of breathing most people use when they are speaking, as it does allow for better expansion than clavicular breathing, providing more power to the voice. However, the ideal breath pattern, for speaking, resting, and exercising, is belly breathing (described below).

Belly breathing. Belly breathing involves using your diaphragm muscle to its fullest range of motion (ROM), which swells your belly on the inhale, like a balloon being inflated. When you exhale, your diaphragm relaxes, allowing your belly to deflate. Belly breathing is the most calming mode of breathing, as it triggers your parasympathetic nervous system (for more information on the parasympathetic nervous system, click here). Please note, there is a subtype of belly breathing, known as abdominal-thoracic breathing. In abdominal-thoracic breathing, your diaphragm first contracts maximally, making your belly rise and expand. This expansion then transitions to your rib cage, where your external intercostals contract to maximally expand your rib cage. Belly breathing is the most efficient method of intake for supporting your voice when speaking and singing and when you are exercising. And, the good news is that if you practice belly breathing, you can get better at it (more on this in parts 2 and 3 of this series). Belly breathing is the breathing style that will be discussed throughout this series.

Relationship Between Breathing and Emotional/Psychological State

Our breath quite literally affects how we feel emotionally. When you take quick, shallow breaths (especially from the shoulder area - i.e. "clavicular breathing"), this breath pattern tells your nervous system that you are stressed and in potential danger. This activates your sympathetic nervous response, making you feel alert and ready to respond to danger. If you were in legit danger, like running away from a crazy person, this would be a fantastic response! However, in our culture, we tend to stay in this heightened sympathetic state, due to poor breathing and movement practices, which is not healthy for the body. When your sympathetic nervous system is activated, a flood of stress hormones (e.g. cortisol) gets released into your bloodstream. These stress hormones can create disease in your body if they are chronically elevated in your bloodstream, which can occur with overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system. For example, high levels of cortisol is associated with depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions. Additionally, your sympathetic nervous system increases your heart rate and blood pressure, leading to all the health issues therein.

Conversely, when you take slow, long, deep breaths (especially using the diaphragm to its maximum ROM - i.e. "belly breathing"), that breath pattern tells your nervous system that you are safe and secure. Specifically, the slow, deep breath stimulates your Vagus nerve (your 10th cranial nerve). This nerve is partly responsible for controlling your parasympathetic nervous system (i.e. your "rest, digest, and repair" system). The increased activity in your Vagus nerve reduces your sympathetic activity (i.e. your "fight, flight, or freeze" system), so you actually feel calmer, more relaxed, and safer. When your parasympathetic system is activated, your body is able to digest food, repair damaged cells and tissue, connect meaningfully with others, and learn new skills. This helps your entire physiology, and psychology, to operate much more smoothly and efficiently. Thus, it is important to know how to activate your Vagus nerve through your breath. Throughout the remainder of this series, we will explore why belly breathing is the preferred mode of breath and how to practice belly breathing, so you can be just as calm, cool, and relaxed as this adorable sloth below.

Summary

Respiration (i.e. breathing) occurs from the coordinated actions of various muscles, your lungs, and your nervous system. The flow of air in and out of your lungs happens due to Boyle's law and pressure differences between the inside of your lungs and outside of your body. Various muscles contract to produce different types of breathing. The diaphragm muscle is always active during breathing; however, many people do not activate their diaphragm to its fullest ROM. Muscles of the chest, abdomen (or belly area), back, and neck may contract during breathing based on the mode of breath, emotional state, and/or activity level of a person. There are three modes of breathing - clavicular, thoracic, and belly breathing. Belly breathing is by far the most calming breath pattern, and it provides the best support for speech, singing, exercise, and overall health/wellbeing. Clavicular breathing is definitely the most up-regulating of the breathing patterns, but it is unfortunately very common. Thoracic breathing is okay sometimes in order to help the thoracic spine and ribs get a little movement and to stabilize your spine during intense physical exertion, but using thoracic breathing as the primary breath mode can also be up-regulating to your nervous system. The type, rate, and depth of your breath affects how you feel emotionally. When your breath is fast and shallow, it activates your sympathetic nervous system (by inhibiting your Vagus nerve) causing you to feel stressed out, panicked, and highly alert. When your breath is slow and deep, it activates your parasympathetic nervous system (by stimulating your Vagus nerve), causing you to feel calm, safe, and relaxed.

Part 2 of this series will examine why belly breathing is so much better for your body's functioning than the other modes of breathing, and part 3 will describe various ways to perform belly breathing. As always, the information presented in this blog post is derived from my own study of neuroscience, human movement, and breathing physiology. If you have specific questions about your breathing or beginning a breathing practice, please consult with your physician. If you are interested in private yoga sessions with me, Jackie, you can book services on my website ("Book Online" from the menu at the top of the page), or you can email me at info@lotusyogisbyjackie.com for more information about my services. Also, please subscribe to my website so you can receive my weekly newsletters (scroll to the bottom of the page where you can submit your email address). This will help keep you "in-the-know" about my latest blog releases and other helpful yoga and wellness information. Thanks for reading!

~Namaste, Jackie Allen, M.S., M.Ed., CCC-SLP, RYT-200, RCYT

References:

Ferreria, J.B. et al. (2013). Inspiratory muscle training reduces blood pressure and sympathetic activity in hypertensive patients: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Cardiology. 166: 61 – 67.

Kim, E., and Lee, H. (2013). The Effects of Deep Abdominal Muscle Strengthening Exercises on Respiratory Function and Lumbar Stability. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 25: 663 – 665.

Krowiac, S. (2020). Respiratory Diaphragm Function: Understanding the Muscle that Powers Breath. Tune Up Fitness® Blog. Article link here.

Ma, X. et al. (2017). The Effect of Diaphragmatic Breathing on Attention, Negative Affect and Stress in Healthy Adults. Frontiers in Psychology. 8: 1 – 12.

McFarland, D.H. (2009). Netter's Atlas of Anatomy for Speech, Swallowing, and Hearing. Mosby Elsevier.

Miller, J. (2014). The Roll Model: A Step-by-step Guide to Erase Pain, Improve Mobility, and Live Better in Your Body. Victory Belt Publishing, Inc.

Stemple, J.C. et al. (2010). Clinical Voice Pathology: Theory and Management. Fourth Edition. Plural Publishing.

Stavroula, S. et al. (2016). The effectiveness of a stress-management intervention program in the management of overweight and obesity in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Molecular Biochemisty. 5(2): 63 – 70.

Comments